Deep in her heart, Natalie* had always known that her binge drinking during the first weeks of pregnancy had affected her little boy’s development. She’d spent enough fearful evenings online, researching the causes of his unmanageable tantrums, to know that Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) was more than a possibility. But no amount of mental preparation could have lessened her distress at hearing the doctor’s diagnosis in August 2018.

“The doctor struggled to find the words, she told me that they weren’t going to judge and that I shouldn’t blame myself,” says Natalie. “[But] I asked her not to sugar coat it.”

While four-year-old Luca played in the corner of the room at the Gold Coast clinic, Natalie was told that her beautiful boy did in fact have FASD, a devastating brain injury caused by alcohol exposure during pregnancy.

Even with the intervention of specialists, it’s likely that Luca will have impulse control issues, destructive behaviour and developmental delays for the rest of his life. He will probably struggle at school; his opportunities will be limited. But worst of all, Natalie knows that all of these challenges were entirely preventable.

FASD is a devastating brain injury caused by alcohol exposure during pregnancy

On the pill and in a casual relationship, Natalie discovered she was pregnant at eight weeks’ gestation. “I don’t know why the pill failed,” she says. “I was working as a bar tender. I had no responsibilities [and] I didn’t have a car so didn’t have to worry about staying under the limit.” Although Natalie stopped drinking as soon as she got pregnant, she was concerned about how all the alcohol she’d drunk might affect her baby; she estimates she consumed nearly 70 drinks in those first eight weeks.

This is not a scare story. In Australia, 59 per cent of women admit to having consumed alcohol while pregnant – and the vast majority of their babies are born healthy.

But what some experts now believe is that FASD – often regarded as an affliction confined to disadvantaged communities – is far more widespread than previously thought. In fact, estimates indicate that 2-5 per cent of Australian children are affected by FASD. In other words, one in 13 pregnancies where women consume alcohol while pregnant.

In November last year, the federal government released a Strategic Plan that suggested ways to raise awareness of the danger of consuming alcohol while pregnant, and mandatory labelling on alcoholic drinks will come into effect later this year. But there is evidence FASD remains woefully underdiagnosed, particularly among vulnerable populations. In WA, for example, one study found 36 per cent of children in a juvenile detention centre had FASD. Before the study, only two children had been diagnosed.

Estimates suggest that 2-5 per cent of Australian children are affected by FASD

“We suspect that there’s a lot of undiagnosed FASD,” says Elizabeth Elliott, Professor in Paediatrics and Child Health at the University of Sydney and a board member of The National Organisation for FASD (NOFASD). Sometimes, FASD is confused with other neurological conditions. “It’s possible that there are kids out there with alternative diagnoses because no one’s ever asked the question about alcohol and pregnancy.”

Traditionally, FSAD was diagnosed on the basis of physical characteristics such as a thin upper lip and a smaller gap than usual between the eyes. Yet only 17 per cent of FASD sufferers have these facial features. The rest have neurological and emotional issues that can be harder to identify as FASD.

NOFASD estimates that there are more children affected each year by FASD than Autism Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, Spina Bifida, Cerebral Palsy and SIDS combined.

Neither is drinking during pregnancy purely an indigenous issue. “There are clusters of FASD in communities such as remote aboriginal communities, where there’s been high-level drinking as a way to deal with historic trauma and significant disadvantage,” says Elliott. “But we have to get the message out that [FASD] is problem across our society.”

“We know from our National Household Survey and other research that the women who drink the most [generally] are highly educated and have a higher socioeconomic status,” she continues.

While most women know they shouldn’t drink while pregnant, there’s a widespread belief – including among many health professionals – that one of two drinks a week makes no difference. “Someone told me the other day that she has a high-risk pregnancy and her obstetrician said, ‘Oh look, a few drinks will help you relax,’” says Elliott.

The truth is that there is no safe level of alcohol during pregnancy, says Elliot who explains that it is impossible to determine individual risk. “You and I might have the same amount to drink, but we’re different ages, have different liver function, different body composition and really importantly – different genetics for metabolising alcohol,” she explains. “Alcohol readily crosses the placenta. When a mother consumes alcohol during pregnancy, the blood alcohol of the foetus is the same, or higher than the mother’s.”

The Australian Medical Association estimates that up to 50 per cent of Australian women experience an unplanned pregnancy – which is one of the reasons that nearly 60 per cent of pregnancies are alcohol-exposed. “It’s a really tricky issue,” admits Elliot. “We’ve got to make it clear to women that there is a potential for harm, but also reassure them that unless they’ve been drinking heavily then it’s unlikely they’ve done harm.”

Nearly five years after seeing the blue lines appear on her pregnancy test, Natalie is still coming to terms with the damage her drinking caused.

Luca has serious behavioural issues including developmental delays and wild, violent tantrums. “He is a very violent child and incredibly strong for a four-year-old. He’s bitten me hard enough to break skin and make me bleed. He has thrown rocks at our dog. He tried to cut the cat’s head off with a pair of scissors,” says Natalie. “He has broken doors, put holes in the walls, broken countless toys.”

Understandably, the emotional toll of raising Luca is huge. “It is mentally, physically and emotionally draining. He needs full-time one-on-one support.”

It’s tricky. We’ve got to make it clear to women that there is a potential for harm, but also reassure them that unless they’ve been drinking heavily then it’s unlikely they’ve done harm

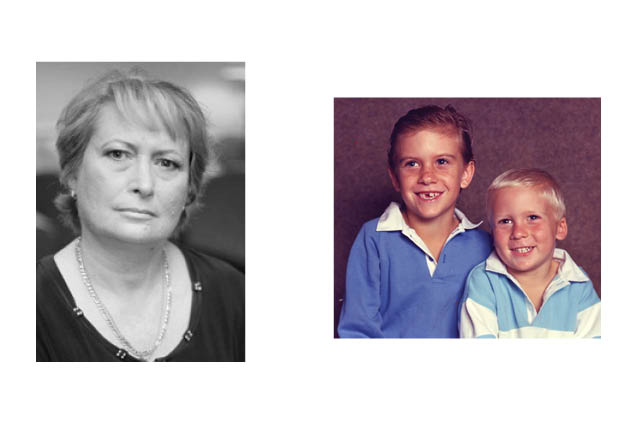

Anne Russell, now 65, understands Natalie’s situation all too well. Twenty years ago her sons, then aged 17 and 20, were officially diagnosed with FASD. While Anne knew deep down that it was likely her drinking had damaged her boys, the diagnosis still came as a blow. “It meant that I couldn’t deny it anymore,” she says.

“I just sobbed, it was like I’d run them over,” she says, her voice shaking. “There is nothing worse that a mother could do to her child. It was the end of what I’d always wanted for my children. They wouldn’t go to university. They wouldn’t be able to hold down a job.”

While it is impossible to reverse FASD, Anne, a recovering alcoholic (sober for 21 years) has spent the years post-diagnosis advocating for her sons and reaching out to support others facing the same difficulties.

In 2007 she set up the Russell Family Foetal Alcohol Disorders Association (RFFADA) to help support the thousands of Australian families living with FASD. “Parents are feeling inadequate, they’re developing their own mental health problems. And the kids are being rejected.”

Anne’s youngest son has followed what she calls a “typical trajectory” for a child with FASD. “He dropped out of school, he has mental health problems, drug and alcohol issues, he has been in prison, and recently, he’s had suicide ideation. It’s a really horrible condition,” she says.

In contrast, Anne’s eldest son has been affected physically – he has temporal lobe epilepsy, he has had a tumour in his jaw and his teeth have been a problem. “The difference between my two children seems to be related to when and how much I drank,” Anne reflects.

Despite the fact here’s no cure for FASD, a diagnosis doesn’t necessarily seal a child’s fate. “Early intervention is key to giving children a better chance at a normal life,” says Associate Professor Doug Shelton, clinical director at Gold Coast Health.

“We know that children aged between three and seven with undiagnosed FASD fall behind on foundational skills such as self-control, ability to plan, organise and follow instructions. Children with FASD aren’t wilfully disobedient but are unable to learn what is proper behaviour,” he adds.

Since the Gold Coast FASD clinic opened in 2014, Dr Shelton and his team have diagnosed around 200 children. That’s just a small fraction of the cases that are out there, he says. But waiting lists for the Gold Coast Clinic can reach two years and there are only a handful of this type of specialist clinic in Australia.

Meanwhile, traditional attitudes to alcohol and pregnancy persist, even in the medical profession. Research published in the journal Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research found that midwives and nurses who don’t understand the risks of FASD are less likely to ask pregnant women about their drinking habits.

“We have a big job to do in our own back yard,” says Dr Steve Robson, president of the Australian and NZ college of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Responsibility for abstinence shouldn’t lie just with women, though. Recently, celebrity personal trainer Sam Wood posted on Instagram that he would give up alcohol to support his partner – a move encouraged by initiatives such as the Pregnant Pause, which enlists a pregnant woman’s friends and relatives to ‘Be a hero, take zero’. “If everyone around you, your family and partner, is drinking it can feel very isolating,” says Robson, who is a Pregnant Pause ambassador. “It makes you very vulnerable to having a drink or being persuaded to ‘just have one’.”

The Pregnant Pause goes some way to acknowledging that FASD is a community problem and not the sole responsibility of mothers. But to turn the tide of FASD experts believe we need to face up to a culture that is tolerant of excessive drinking. “Until we can change society’s acceptance of binge drinking then it’s going to be very difficult to change this problem of drinking and pregnancy,” says Elliott.

Understandably, Natalie Whitton is unequivocal in her belief that it’s “not OK to drink while pregnant.”

“I don’t care if your mum drank and you’re OK,” she adds. “Why take the chance?”

4 Comments