In the end it wasn’t the murder weapon – an axe – or the panicked Triple Zero call that most disturbed me. Of all the evidence in the case of Tara Costigan’s death, the piece that has haunted me more than any other is possibly the most innocuous looking.

It is the CCTV footage of Tara’s ex-partner Marcus Rappel driving up and down her street for an hour before he burst into her home and became a murderer.

In the tape, Marcus’ white ute slows down, inches forward, second-guesses, before driving off. On it goes, down and up, up and down. Every time I watch that piece of film, I feel a flutter of cruel hope that the vehicle will not return. But always it comes back again – until at last, with a single swing of the wheel Marcus enters Tara’s driveway and the film ends.

For the past three years, Tara Costigan has laid claim to my thoughts and drifted through my dreams.

I first read about her murder on my phone, one hand grasping an overhead stirrup on the 57 tram to Flinders Street, back in early 2015. Details were slow to trickle through and for a couple of days remained more or less fixed: a 28-year-old mother of three, found dead in her Canberra home with an axe close to her body. A 40-year-old man found at the scene was ‘assisting police with their enquiries’.

The situation became yet more horrific when it emerged that all three of the victim’s children, one of whom was barely a week old, were present at the time their mother was murdered.

From the outset Tara stirred my curiosity. I suppose there was a sort of demographic sympathy at work – Tara was a year younger than me, an Australian woman in her late twenties who had lived in the same city as I used to. I wondered how close we might have come to crossing paths, or even if we had. I wondered, too, about her backstory – her childhood and where she came from.

But as I researched, immersing myself in the sad stockpile of evidence pertaining to her murder as well as the everyday evidence that offered clues about her character, I realised there was another factor, another similarity between us.

When Tara was killed she had just taken out a DVO (domestic violence order) against Marcus, who had become verbally abusive. The pair had been together for 14 months, and she had just given birth to their baby daughter, Ayla. He was never physically violent; in fact the day before her murder, Tara had assured her uncle that she was at no risk of physical harm because Marcus had never hit her before.

Tara had understood that applying for a DVO was the natural and appropriate step, but her longstanding hope was that the relationship with Marcus would miraculously improve. She was not applying for an order against a man she wanted nothing to do with; she was applying for an order against a man she still adored, but whose behaviour she understood needed to be stopped.

Ending an abusive relationship can be extremely difficult, for reasons both practical and emotion. As I learnt more about Tara’s inner struggle, I felt empathy for that mindset which can seem so incomprehensible to family and friends looking on.

It’s a mindset I well remember.

I was drawn to Kevin* when we met; he was spectacularly self- assured. I was starry-eyed, delirious with excitement.

Then, one winter night we were on our way home from somewhere, and I was looking forward to eating dinner next to the heater. I suddenly remembered the tin of sardines in my bag that I hadn’t eaten on my lunch break. I went to open it.

Kevin turned to me. ‘Don’t open that, baby, you’ll stink out the car for a week.’

‘But I’m starving.’

I guess I thought that when I opened the tin, he’d just roll his eyes and shake his head. When he slammed his fist against the steering wheel I froze. When we got home, I ran inside and stood in the bedroom while he paced the hallway, beer in hand. He was screeching, raging – inexhaustible. I was a little bitch, a fucking whore, a fucking little cunt. He punched the wall until the plaster gave. I slipped down the hallway and locked myself in the toilet. I don’t remember how long I stayed there, but his tirade lasted most of the night.

Kevin never apologised, not for that first night of madness nor for any of the others that followed. And it happened again, and again and again.

He never apologised, not for that first night of madness nor for any of the others that followed

Nights were the most dangerous time; if he was drinking, the risk of a hellish few hours was much greater. As the empty beer bottles accumulated something as simple as a heavy sigh or a roll of the eyes could set him off until dawn.

Driving home one night, he pointed to the windscreen. ‘Do you know that I can put your head through this if I choose?’

He might have, but he did not. The fact that I remained physically unmarked became a crucial, if unremarked upon, factor. In his eyes it was perhaps the most powerful testament of love that he could offer. In my eyes, it was evidence that I didn’t have it so bad, after all.

Why didn’t I walk away sooner? I didn’t know the answer, beyond the pale-sounding fact that I had fallen for him hard. I believed that his goodness was fundamental, that his bad behaviours were as dark clouds passing over the moon.

Why didn’t I walk away sooner? I don’t know the answer beyond the fact that I had fallen for him hard

Simultaneously, I was scratching my head – what on earth had become of my fiery set of principles? I knew exactly what sort of advice I would give a girlfriend.

As a rule, I didn’t tell people what was happening. Not because I was embarrassed but because of the rigid, tremendoussentiment I thought was loyalty. In truth I suspect it was fear that stopped me from speaking out – fear that pressure might beput upon me to end the relationship, or that Kevin would somehow find out and resent me for blackening his name (God forbid that his name should be blackened).

I knew that it had to stop. Of course I did. I knew too that all I had to do to make it stop was walk away. I was my own redeemer.

Then, in the midst of my turmoil, someone close to me was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer. Every hour that I could spend at the hospital – and later, the hospice – I did.

As someone dear to me lost the capacity to eat – as we resorted to dipping a swab in a cup of water and wetting the insideof their cheeks – I was beginning to feel as though anaesthesia were coursing through me.

I no longer had the emotional energy to withstand Kevin’s tirades. I ended the relationship – and although Kevin triedmany times to persuade me to return, he eventually gave up. I understood that I had done the right thing, but I was ashamed of the fact that I had only found the courage to do so at a time when I was emotionally numb.

It was my experience of emotional abuse – of being urged, time and again, to believe how little I amounted to – that kindled my initial interest in Tara Costigan’s story.

I didn’t know what her own experience had looked or sounded like, but I knew how devastating it was to be so thoroughly disparaged by a man. I knew how confused I had been throughout that period, how lost and stripped of confidence. I knew what it was like to have a family who were desperately worried. And I suspect that there were times when Tara and I knew a similar despair.

Again and again, the question ran through my mind – how had Tara’s death happened? How had the verbal abuse culminated in murder?

In researching Tara’s story, I found a 2018 report from the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network which revealed that 76.2 per cent of 105 males who killed female domestic violence victims had been physically violent towards them previously. It was a large number, but it left nearly a quarter of cases in which there was no reported or anecdotal history of physical violence.

I was also interested to discover that it’s commonly believed among domestic violence advocates that while not all verbal abuse becomes physical, all physical abuse begins with verbal violence.

I couldn’t help wondering how a better awareness of the statistics might have affected my thinking during my relationship with Kevin.

When I look back on that time I often marvel at my own naivety – my certainty that I understood if not the dynamics that left me utterly devastated a few nights a week, then at least the exact ways in which the damage would be wreaked.

Of course, there is no way of knowing what would have happened if I had stayed; I might still be walking around without a single bruise on my body, a body which by now would be the husk of a woman whose sense of self had been pulverised.

It’s also possible – probable, even – that I would have considered the more frightening statistics to be wholly irrelevant to my circumstances.

I wondered how Tara’s mindset might have changed had she known the statistics.

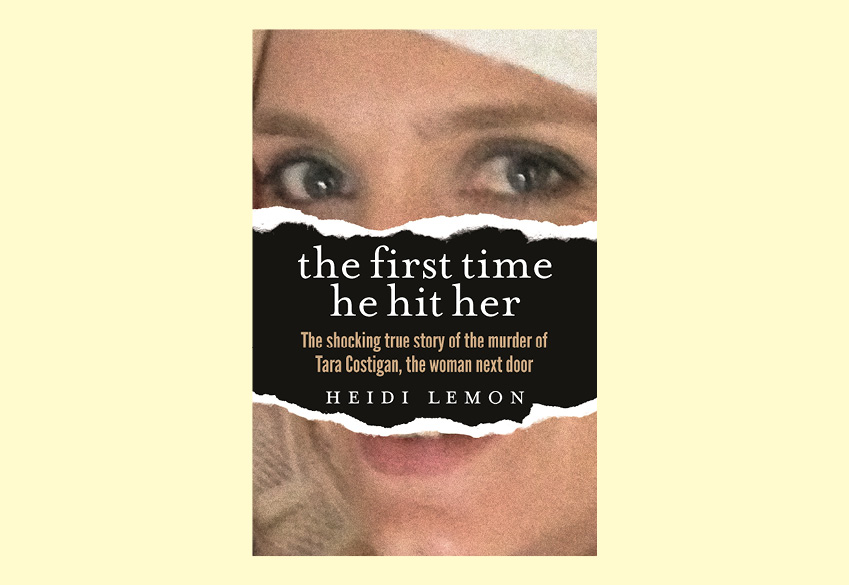

This is an edited extract from The First Time He Hit Her by Heidi Lemon. Published by Hachette Australia RRP $32.99

No Comments